Everything about Incoterms

What are incoterms?

An incoterm or “International Commercial Term” represents a universal term. It defines a transaction between importer and exporter, so that both parties understand the tasks, costs, risks and responsibilities, as well as the logistics and transportation management from the exit of the product to the reception by the importing country.

Incoterms are all the possible ways of distributing responsibilities and obligations between two parties. It is important for buyer and seller to predefine the responsibilities and obligations for transport of the goods.

Main responsibilities and obligations:

- Point of delivery: here, the incoterms defines the point of change of hands from seller to buyer.

- Transportation costs: here, the incoterms defines who pays for whichever transportation is required.

- Export and import formalities: here, incoterms defines which party arranges for import and export formalities.

- Insurance cost: here, incoterms define who takes charge of the insurance cost.

Incoterms rules comprehend a total of eleven terms published by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) based in Paris which define the conditions of supply of goods in international sales transactions.

The first edition was published in 1936. Subsequently they have been making several revisions and updates (usually every ten years) to the one currently in force which is Incoterms 2020.

What are incoterms used for?

The purpose of Incoterms is to precisely define three aspects of international trade:

- The allocation of logistics costs between seller an buyer.

- The transmission of risks in transporting the goods.

- The documents and customs formalities necessary for export and import operations.

What is the purpose of incoterms?

Frequently, parties to a contract are unaware of the different trading practices in their respective countries. This can give rise to misunderstandings, disputes and litigation with all the waste of time and money that this entails.

In order to remedy these problems the International Chamber of Commerce first published in 1936 a set of international rules for the interpretation of trade terms. These rules were known as «Incoterms 1936». Today the standard is “Incoterms 2010.”

The purpose of Incoterms is to provide a set of international rules for the interpretation of the most commonly used trade terms in foreign trade. Thus, the uncertainties of different interpretations of such terms in different countries can be avoided or at least reduced to a considerable degree.

What are the advantages of using incoterms?

As they stand today, there are 11 main terms and a number of secondary terms that help buyers and sellers communicate the provisions of a contract in a clearer way; therefore, reducing the risk of misinterpretation by one of the parties.

Incoterms govern everything from transportation costs, insurance to liabilities. They contribute to answering questions such as “When will the delivery be completed?” “What are the modalities and conditions for transportation?” and “How do you ensure one party that the other has met the established standards?

Having said that, it is important to remember that there are also limits to Incoterms. For example, they do not apply to contractual rights and obligations that do not have to do with deliveries. Neither do they define solutions for breach of contract.

The history of incoterms

The FOB Incoterm was the first Incoterm to be created. And even though its origin traces back over more than two centuries, Incoterms as they are now weren’t actually created until 1936 by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC).

Since then, the international transportation community has gone through many changes. To adapt, there have been new and improved editions of the Incoterms like the ones introduced in 1953, 1967, and 1976.

But over the past five decades, revisions have been implemented at the turn of every decade and tend to stay in effect for the entire decade, such as Incoterms 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2020.

The importance of Incoterms and how they facilitate world trade cannot be denied. When Incoterms were first introduced, they applied only to 13 countries. Eight revisions later, they are now widely used in over 140 countries and can be found in 31 different languages.

- 1812: The FOB Incoterm was first used in the British Courts in 1812. This was later known as the forefather of the famous transport clauses – Incoterms.

- 1895: 83 years later, thanks to the expansion of world trade, a second Incoterm was born.

- 1936: The birth of Incoterms as we know them today. In 1936, the ICC published the first edition with six Incoterms and rules on how to interpret them. For the first time in history, there was a global effort to standardize international trade practices.

- 1953: The first Incoterms revision came after WWII. Rail transportation was on the rise and three new Incoterms were introduced for non-maritime transport: Free on Rail, Free on Truck, and Delivered Costs Paid. EXW Incoterm was also added.

- 1976: The FOB Airport Incoterm (Free on Board Airport) was introduced for air freight to avoid confusion with the FOB Incoterm.

- 1980: Due to the proliferation of freight traffic in containers, two new Incoterms were added: FRC and FCI, which are known today as FCA and CIP respectively.

- 1990: A complete revamp of Incoterms to adapt to inter-modal transportation. Changes were made to accommodate the increasing use of Electronic Data Interchange (EDI).

- 2000: In 2000, Incoterm formats were simplified for clarity and to better distribute responsibilities for customs clearance.

- 2010: Four Incoterms (DAF, DES, DEQ, DDU) were eliminated and two new ones (DAT and DAP) introduced, bringing the number of Incoterms to 11. Modifications were also made so that buyer and seller were obliged to cooperate in the exchange of information as a security measure.

- 2020: Introduction of a new Incoterm, Cost and Insurance (CNI), and the removal of EXW and FAS as well as a more simplified version to aid comprehension and application of each Incoterm.

Incoterms versions or revisions. Why?

The main reason for successive revisions of Incoterms has been the need to adapt them to contemporary commercial practice.

Thus, in the 1980 revision the term Free Carrier (now FCA) was introduced in order to deal with the frequent case where the reception point in maritime trade was no longer the traditional FOB-point (passing of the ship’s rail) but rather a point on land, prior to loading on board a vessel, where the goods were stowed into a container for subsequent transport by sea or by different means of transport in combination (so-called combined or multi modal transport).

Further, in the 1990 revision of Incoterms, the clauses dealing with the seller’s obligation to provide proof of delivery permitted a replacement of paper documentation by EDI-messages provided the parties had agreed to communicate electronically. Needless to say, efforts are constantly made to improve upon the at the seller’s own premises (the «E»-term Ex works); followed by the drafting and presentation of Incoterms in order to facilitate their practical implementation.

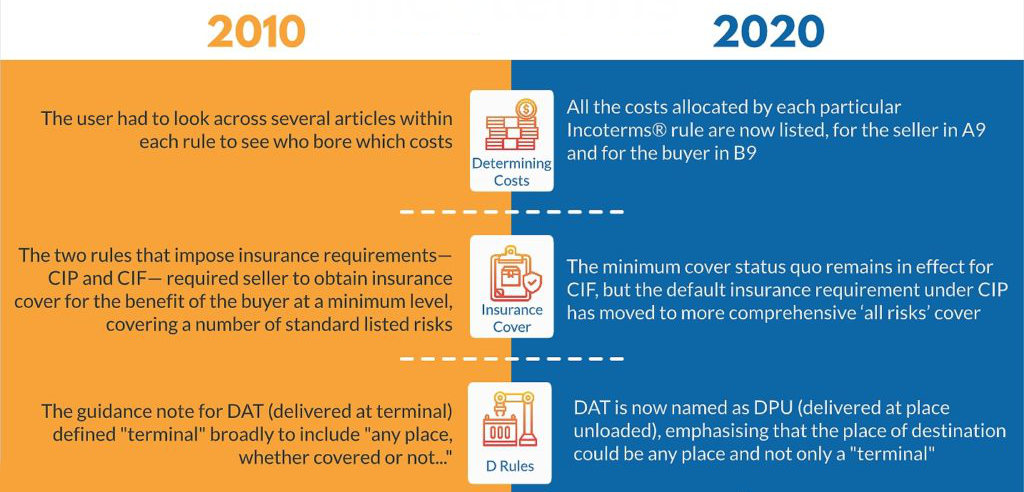

Incoterms 2010 vs Incoterms 2020. What changed and why?

Incoterms are revised periodically. The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) reviews and updates the Incoterms rules every ten years – the previous edition was published in 2010. The current is called Incoterms 2020.

The changes made in this latest edition – the ICC’s Incoterms® 2020 – address mainly increased security requirements, improved clarity on cost allocation as well as insurance concerns.

According to the International Chamber of Commerce, all contracts made under Incoterms 2010 remain valid even after 2021. The answer is simple: each contract is governed by the version of Incoterms rules that was referred to in that contract. If the contract referred only to Incoterms rules but not to a specific year, then the Incoterms rules version in force at that time of contracting would most likely be applied in the event of a dispute. Best practice is always to refer to the most recent revision, e.g. Incoterms 2020.

Although it is recommended to use Incoterms 2020, parties can agree to choose any version of the Incoterms rules. It is important, however, to clearly specify which version you have chosen. Below are the main differences in Incoterms 2010 and Incoterms 2020.

1. Bills of lading:

FOB (free on board) should not normally be used for container shipments. This is because a seller usually loses control of the container once the container arrives at the port of export before the container is loaded. However, FOB means the seller takes all the risk and cost of the export, port terminal handling charges and loading costs/risks. Sellers should then use FCA (Free Carrier).

However, many sellers still use FOB because the letter of credit from the bank often requires an onboard bill of lading for the seller to get paid. As under FOB the seller is responsible for loading, they have a higher chance of getting an onboard bill of lading.

Therefore, to try and help people to use FCA, FCA has changed to allow the buyer and seller to agree that the seller will get an onboard bill of lading.

2. Insurance under CIF (carriage insurance and freight) and CIP (carriage and insurance paid to):

The Incoterms® rule, CIP means that the seller is only responsible for delivery of the goods to the carrier but pays for the carriage and insurance of the goods to the named destination. CIF is the same, except that it can only be used for maritime transport (delivery is onto a ship and the destination needs to be a port).

In Incoterms® 2020, CIF keeps the same insurance requirements as in Incoterms® 2010, but CIP has increased the level of insurance required to be obtained by the seller. This is due to the fact that CIF is more often used with bulk commodity trades, and CIP is more often used for manufactured goods, and manufactured goods tend to require a higher level of insurance.

Although CIF and CIP require the seller to obtain insurance, it is recommended that parties consider whether additional insurance coverage is required to reflect the potential risk of damage to the goods during transport.

If you use CIF or CIP, you need to review to see if that is still the correct approach.

3. DAT (delivered at terminal) has changed to DPU (delivered at place unloaded):

In Incoterms® 2010, DAT means the goods are delivered once unloaded at the named terminal. As DAT limits the place of delivery to a terminal, in Incoterms® 2020, the reference to terminal has been removed to make it more general. DPU means delivered at place unloaded (which can now be used for all modes of transportation). There is no other change.

If you use DAT Incoterms® 2010, then change over to DPU Incoterms® 2020.

4. Security Requirements:

In recent years, transport security requirements have become more prevalent in international trade, and Incoterms® 2020 reflects such a change by detailing security requirements for each Incoterms® rule. For example, CPT (carriage paid to) includes a specific requirement that the seller must comply with any security-related requirements for transport to the destination. These security requirements bring cost and risk delay if not fulfilled by the parties.

Incoterms categories or types

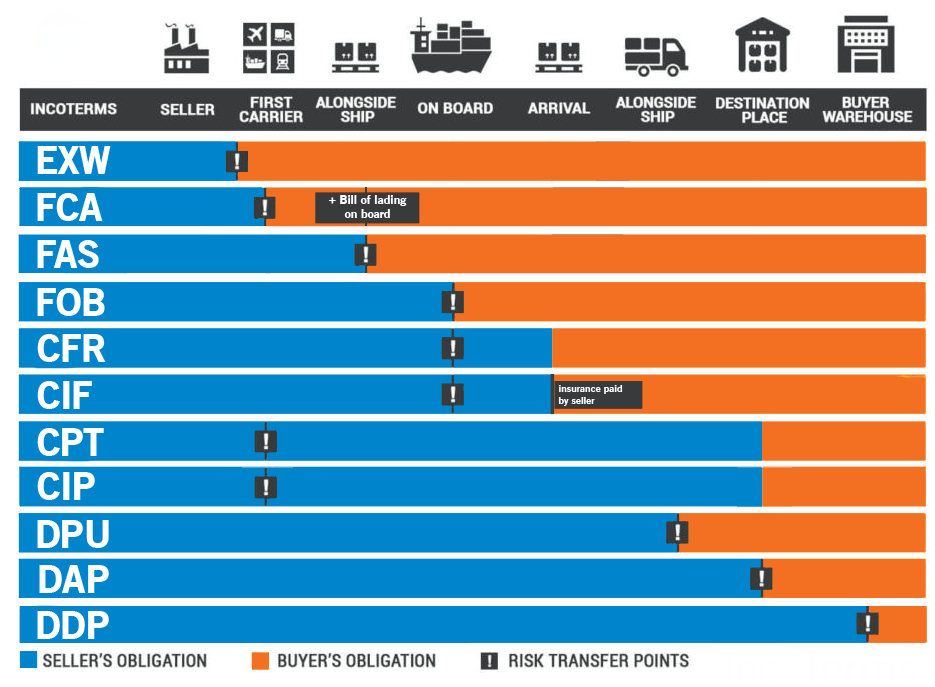

The 11 Incoterms 2020 rules are presented in two distinct classes:

The first class includes the seven Incoterms 2020 rules that can be used irrespective of the mode of transport selected and irrespective of whether one or more than one mode of transport is employed. EXW, FCA, CPT, CIP, DAT, DAP and DDP belong to this class.

They can be used even when there is no maritime transport at all. It is important to remember, however, that these rules can be used in cases where a ship is used for part of the carriage.

In the second class of Incoterms 2020 rules, the point of delivery and the place to which the goods are carried to the buyer are both ports, hence the label “sea and inland waterway” rules. FAS, FOB, CFR and CIF belong to this class.

Under the last three Incoterms rules, all mention of the ship’s rail as the point of delivery has been omitted in preference for the goods being delivered when they are “on board” the vessel. This more closely reflects modern commercial reality and avoids the rather dated image of the risk swinging to and fro across an imaginary perpendicular line.

- All types of transportation (including maritime):

- EXW, Ex Works

- FCA, Free Carrier

- CPT, Carrier Paid To

- CIP, Carrier and Insurance Paid To

- DAT*, Delivery at Terminal

- DAP*, Delivery at Place

- DDP, Delivery Duty Paid

- Fluvial and maritime transportation:

- FAS, Free alongside Ship

- FOB, Free on Board

- CFR, Cost and Freight

- CIF, Cost Insurance and Freight

* DAT and DAP can be equally used for transactions that involve the use of one or several types of transportation.

List of all incoterms 2020

There are currently 11 incoterms in use. Below you’ll find the meaning as well as a short overview of the responsibilities involved for buyer and seller for each of them. For more details, click on the link of each incoterm to lead you to a page with more detailed information.

1. CIF (Cost, Insurance and Freight)

CIF means that the seller delivers when the suitably packaged goods, cleared for export, are safely stowed on board the ship at the selected port of shipment. The seller must prepay the freight contract and insurance.

2. CIP (Carriage and Insurance Paid to)

CIP means that the seller delivers the goods to a carrier or another approved person (selected by the seller) at an agreed location.

The seller is responsible for paying the freight and insurance charges, which are required to transport the goods to the selected destination.

3. CFR (Cost and Freight)

CFR means that the seller delivers when the suitably packaged goods, cleared for export, are safely loaded on the ship at the agreed upon shipping port. The seller is responsible for prepaying the freight contract.

4. CPT (Carriage paid to)

CPT stands for when the seller delivers the goods to a carrier, or a person nominated by the seller, at a destination jointly agreed upon by the seller and buyer. The seller is responsible for paying the freight charges to transport the goods to the named location. Responsibility for the goods being transported transfers from the seller to the buyer the moment the goods are delivered to the carrier.

5. DAT (Delivered at Terminal)

DAT is a term indicating that the seller delivers when the goods are unloaded at the destination terminal. While there is no requirement for insurance, the delivery is not complete until the goods are unloaded at the agreed destination. Therefore, the seller should be wary of the risks that not securing insurance could pose.

6. DAP (Delivered at Place)

DAP means that the seller delivers the goods when they arrive at the pre-agreed destination, ready for unloading.

It is the buyer’s responsibility to effect any customs clearance and pay any import duties or taxes. The seller should be wary of the risks of not securing insurance.

7. DDP (Delivery Duty Paid)

DDP means that the seller delivers the goods to the buyer, cleared for import and ready for unloading, at the agreed location or destination. The seller maintains responsibility for all the costs and risks involved in delivering the goods to the location. DDP holds the maximum obligation for the seller.

8. EXW (Ex Works)

EXW means that the seller has delivered when they place or deliver suitably packaged goods at the disposal of the buyer at an agreed-upon place (i.e. the works, factory, warehouse, etc.). The goods are not cleared for export. From collection, the buyer is responsible for transport, all risks, costs and clearances.

9. FAS (Free Alongside Ship)

FAS stands for when the seller delivers the goods, packaged suitably and cleared for export, by placing them beside the vessel at the agreed upon port of shipment. At this point, responsibility for the goods passes from the seller to the buyer. The buyer maintains responsibility for loading the goods and any further costs.

10. FCA (Free Carrier)

FCA means that the seller fulfills their obligation to deliver when the goods are handed, suitably packaged and cleared for export, to the carrier, an approved person selected by the buyer, or the buyer at a place named by the buyer. Responsibility for the goods passes from seller to buyer at this named place.

11. FOB (Free on Board)

FOB means that the seller delivers the goods, suitably packaged and cleared for export, once they are safely loaded on the ship at the agreed upon shipping port. At this point, responsibility for the goods transfers to the buyer.

What are the most common incoterms?

- EWX (ex works)

- FOB (Free on Board)

- CFR (Cost & Freight)

- DAP (Delivered At Place)

- DDP (Delivery Duty Paid)

Are incoterms mandatory?

Some common misconceptions still abide about Incoterms, however: They are not mandatory.

Rather, Incoterms are contractual terms that buyers and sellers can choose to incorporate, the same as any other contractual term. … Incoterms only apply to the contracts of sale; however, the other contracts do need to match with the Incoterm being used.

Incoterms do not…

- Determine ownership or transfer title to the goods, nor evoke payment terms.

- Apply to service contracts, nor define contractual rights or obligations (except for delivery) or breach of contract remedies.

- Protect parties from their own risk or loss, nor cover the goods before or after delivery.

- Specify details of the transfer, transport, and delivery of the goods. Container loading is NOT considered packaging, and must be addressed in the sales contract.

- Remember, Incoterms are not law and there is NO default Incoterm!

How to use incoterms in a contract?

It is critically important during the tendering process, depending on the type of sourcing, whether strategic, tactical or project, that the terms of sales be discussed upfront and at every stage of the contract-formulation process.

More importantly, all stakeholders should be aware of both the advantages and the disadvantages of each Incoterm in order to be able make appropriate decisions when dealing with international trade transactions.

The following have to be noted before concluding and signing a contract (this is a requirement introduced by the Incoterms 2010 rules):

1. Specify your place of departure or port as precisely as possible:

If both parties agree on the use of a certain port or named place of departure, it is very important to name it as precisely as possible. This will avoid potential disputes as a result of ambiguity regarding the place.

This lack of specifying a place was probably one of the reasons why the experts responsible for the revision decided to incorporate this important point. For example, if both parties agree on FCA Incoterms, it would be advisable to state the arrangement as:

‘Unit 23 Rainbow Industrial Park, Gillette Avenue, Reading, UK as per Incoterms 2010.’

This is very specific and the seller will have a clear understanding that he or she will fulfill his or her obligation only once delivery has taken place to the stated address.

2. The specific Incoterm should be incorporated in the contract of sale:

Incoterms apply only if incorporated in the contract of sale or if they are, for example, mentioned in the offer, the sales conditions, the purchase order, the confirmation of an order or if they are stipulated by the parties in separate agreement.

With the new revised set of Incoterms and their requirements, it is important to note that whenever you want the Incoterms to apply to your contract, legal members who participate as a cross-functional team must make sure that they should make it clear in their contract through such words as:

‘The chosen Incoterms rule including named place or port followed by Incoterms® 2010’.

In addition to this, it must be stressed that when the parties intend to incorporate Incoterms into their contracts of sale, they should always make an expressed reference to the current version of these terms.

3. Appropriate Incoterms must be chosen:

Whenever Incoterms are chosen, it has to be stressed that they must be appropriate to the goods (type, weight, dimensions) that are going to be imported or delivered. In addition, the means of transport (road, rail, air or sea) also plays an influential role in the selection of the appropriate terms of sale.

Certain types of goods cannot be delivered by air because of their excessive weight. However, whichever Incoterm will have been chosen or agreed upon, both parties should always be aware that the interpretation of their contract may well be influenced by customs at a particular port or place being used.

It must be emphasised that all the personnel in a company responsible for concluding the contracts must be well-trained and have a full understanding of the different Incoterms and their implications, because choosing the wrong or an inappropriate Incoterm for a specific situation may be very costly.

4. Be aware that Incoterms rules do not give a complete contract of sale:

It is important to ensure that other contractual obligations are incorporated separately, for example payment terms, transfer of ownership of goods and also the consequences of a breach of contract that are normally dealt with in a service-level agreement (SLA).

If parties make the assumption that all other contractual aspects are covered by a chosen Incoterm, it will have seriously negative repercussions. Many disputes are as a result of the trading community not understanding the importance of creating a contract of sale that looks after the interest of both the seller and the buyer.

Ten common mistakes in using the incoterms rules

Below are some of the most common mistakes made by importers and exporters:

- Use of a traditional “sea and inland waterway only” rule such as FOB or CIF for containerised goods, instead of the “all transport modes” rule e.g. FCA or CIP. This exposes the exporter to unnecessary risks. A dramatic recent example was the Japanese tsunami in March 2011, which wrecked the Sendai container terminal. Many hundreds of consignments awaiting despatch were damaged. Exporters who were using the wrong rule found themselves responsible for losses that could have been avoided!

- Making assumptions about passing of title to the goods, based on the Incoterms rule in use. The Incoterms rules are silent on when title passes from seller to buyer; this needs to be defined separately in the sales contract

- Failure to specify the port/place with sufficient precision, e.g. “FCA Chicago”, which could refer to many places within a wide area

- Attempting to use DDP without thinking through whether the seller can undertake all the necessary formalities in the buyer’s country, e.g. paying GST or VAT

- Attempting to use EXW without thinking through the implications of the buyer being required to complete export procedures – in many countries it will be necessary for the exporter to communicate with the authorities in a number of different ways

- Use of CIP or CIF without checking whether the level of insurance in force matches the requirements of the commercial contract – these Incoterms rules only require a minimal level of cover, which may be inadequate.

- Where there is more than one carrier, failure to think through the implications of the risk transferring on taking in charge by the first carrier – from the buyer’s perspective, this may turn out to be a small haulage company in another country, so redress may be difficult in the event of loss or damage

- Failure to establish how terminal handling charges (THC) are going to be treated at the point of arrival. Carriers’ practices vary a good deal here. Some carriers absorb THC’s and include them in their freight charges; however others do not.

- Where payment is with a letter of credit or a documentary collection, failure to align the Incoterms rule with the security requirements or the requirements of the banks.

- When DAT or DAP is used with a “post-clearance” delivery point, failure to think through the liaison required between the carrier and the customs authorities – can lead to delays and extra costs.